Write what you know.

Despite the simplicity of this suggestion, the idea has quite profound connotations. Time spent considering them would lead us to a lengthy philosophical discussion regarding what we can ever really know. At this moment I am interested generally in a simple division between what we know personally and what we know collectively as a result of the social and cultural stories with which we align ourselves. And specifically how that has impacted on writers of metaphysical fiction in Australia.

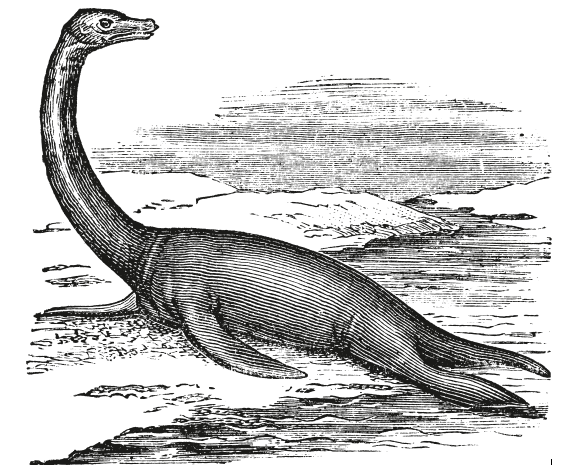

I am writing a children’s historical fiction novel which unfolds beneath the canopy of mythological motifs common to the Irish/Scots Selkie mythos and the water deities of Indigenous Australian cultures, in particular those of the Palawa Aborigines in Tasmania.

Part of the process involves looking at the ways in which writers have approached the metaphysical quality of the Australian landscape since the late 19th Century, and the ways in which they have been ‘successful’ in doing so as writers, and as humans.

The success might be measured by the impact and readership of their creative works, or it may be measured by the degree to which the non-idigenous of those writers were able to include Aboriginal perspectives on the spirit of the land, and resist an appropriation of Aboriginal folklore and mythology.

The issue has a long history of debate , which is ever changing as our views on cultural appropriation become, at last, more sophisticated and respectful.

As a writer creating an historical fiction story set in Tasmania at this moment in time, the preservation of space for Palawa people to tell their own stories touches every aspect of my creative process. And at the same time I am humbled, humoured even, by the realisation, that I, three generations from my Irish grandparents, am yet enamoured by a landscape of folklore that can never exist here in Australia. And being so possessed by such a pixie spell as this, I see it everywhere.

Write what you know.

I don’t ‘know’ Ireland, I’ve never even been there. And yet I do, as so many in the Irish Diaspora experience, feel such an overwhelming familiarity with its pieces all.

As a child I would leaf through Brian Froud’s Faerie book , rather gruesome at times and quite wild in parts. But there I found faces I felt I might know. And as I child, living in the bush, I saw them when I walked, through bracken and ferns and heavy soil, or along the rocky creek edge peering into dark pools of water that smelt like earth and moss, the spray from the water falls secret and timeless.

Images from Brian Froud and Alan Lee’s Faeries

Equally beloved was Dick Roughsey’s The Rainbow Serpent. What a powerful book. Every part of it rang out bold and uncompromising from the pages. It was strange, and unfamiliar, almost intimidating, but maybe it was only that the dry lands of central Australia seemed foreboding to a child.

The wet cool waterways could more easily house the creatures I thought knew, and thus they were there. But now, writing as an educated adult, in an academic context…it cannot just be faeries anymore.

What I have tried to create is something in between, neither fantasy, nor realism, nor even magic realism. A place where the mythos meet, beyond our socio-political wounds and complications. A place where things I know can live. Because , if as they say, all you can really do is write what you know.. . therein some authenticity lies.

As part of the writing process, I am observing interpretations of the natural environment from both children’s and former children ( otherwise known as adults) perspectives, and how the stories we know shape the faces we see. And the doorways still to be opened.

….